How do young people view SAMA? A youth-led participatory video workshop by Paul Cooke in Kolar

What first attracted you to working on Project SAMA?

“It the fundamental ethos of the project, and the ways in which the intervention to be developed was to be rooted in the lived experience of young people. Since 2015 I have been working on a number of projects that have adopted a similar approach to their design and delivery, taking as their starting point the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child, in particular Article 12, which enshrines the right for children and young people to express their view on matters that concern them, and to be listened to. The largest of these projects was ‘Changing the Story: building civil society with and for young people in post-conflict settings’. This was a five year project, funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council and the Global Challenges Research Fund, that worked with academics, NGOs, artists and young people to explore the many and varied ways in which young people use the arts around the world to develop their own programmes that can directly shape civil society in the aftermath of conflict. Over the course of Changing the Story, as the world was hit by a global pandemic, as well as new waves of violence in many of the contexts we were working, the mental health of the young people involved became an ever-more prominent concern for many of the organisations we partnered with, as well as for the young people themselves. It is a common feature of the literature on arts-based development programmes to highlight the therapeutic potential of such work. The arts are frequently constructed as a ‘safe space’ for young people to reflect, not least, upon the mental-health challenges they face. As an arts-practitioner with no professional qualifications in mental health research, therapy or counselling, I have always been very cautious about explicitly exploring this potential. Consequently, I was very pleased to be able to work with researchers in Psychology and clinical mental health professionals who were in a position to reflect up this topic.”

What is your role on Project SAMA?

“It’s all well and good to state the right of children and young people to be heard in discussions about matters that affect them. The challenge is often to provide a space for them to speak, and a forum in which they can be listened to. My role in Project SAMA is to provide one of the ways the project seeks to create this space. Specifically, I work with young people to make short films designed, on the one hand, to give them the opportunity to present their view on the project, to highlight what they see as its particular value or how it can be improved. On the other, my work seeks to generate material that can be used to support the uptake of SAMA by other schools and to raise awareness of the project with relevant policy stakeholders.

My work on SAMA has followed a very tried and tested approach to youth-led participatory video production that goes back to at least the 1960s. Typically in such projects, a filmmaker works with a group of young people, introducing them to the basics of video production (the use of cameras and sound-recording equipment, script production and storyboarding, editing, post production and so on), while also supporting them to reflect upon an issue that is important to them and that they wish to raise with other members of their community. Projects tend to adopt an iterative, ‘learning by doing’, approach, each exercise undertaken by the young people being designed to both help them develop the necessary technical skills for audio-visual communication and to support ever-deeper reflection on the issues they wish to explore and who they think they need to engage in order to create greater awareness of the topic at hand.”

Can you tell us about the youth-led participatory film-making in Project SAMA?

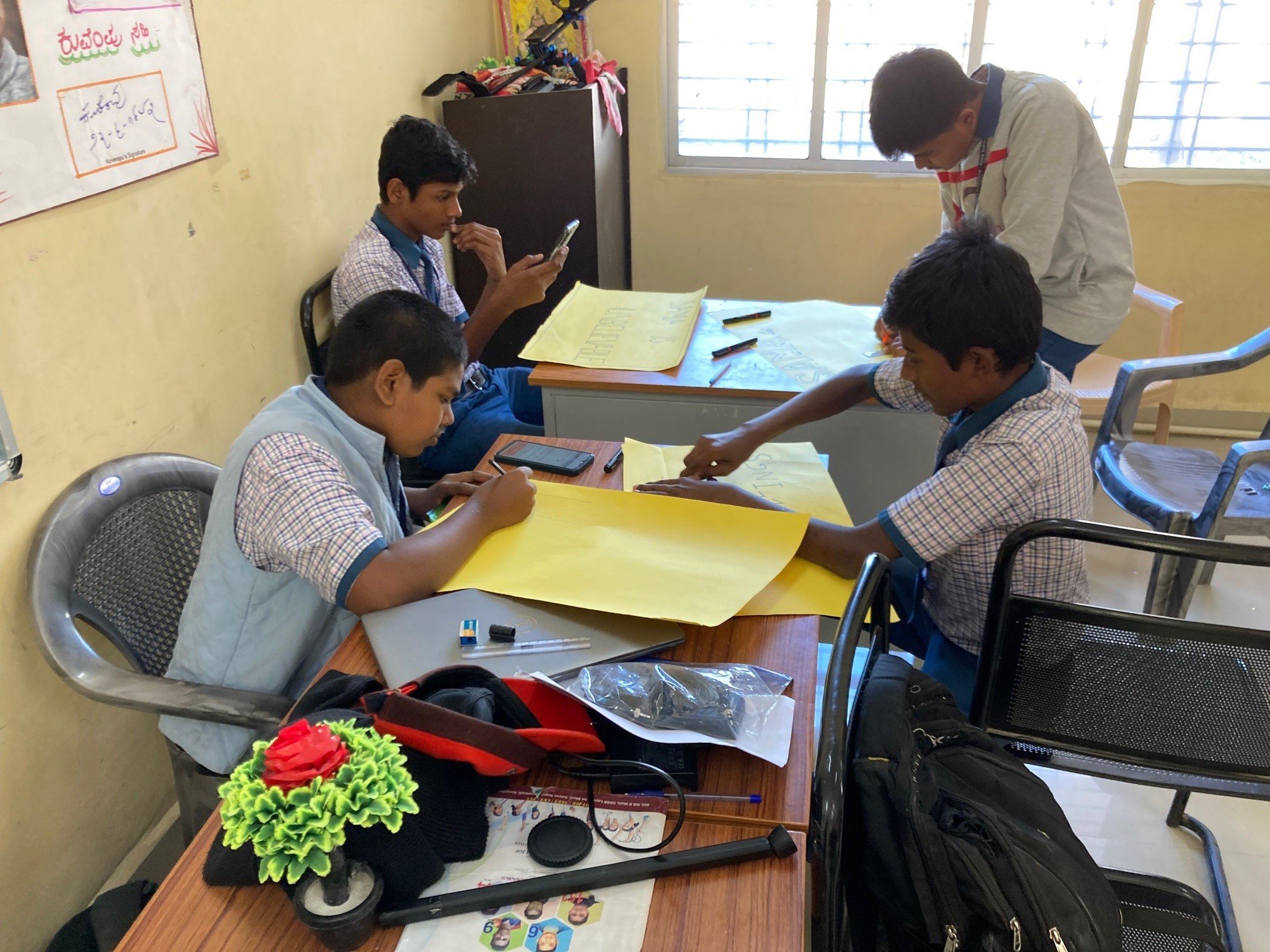

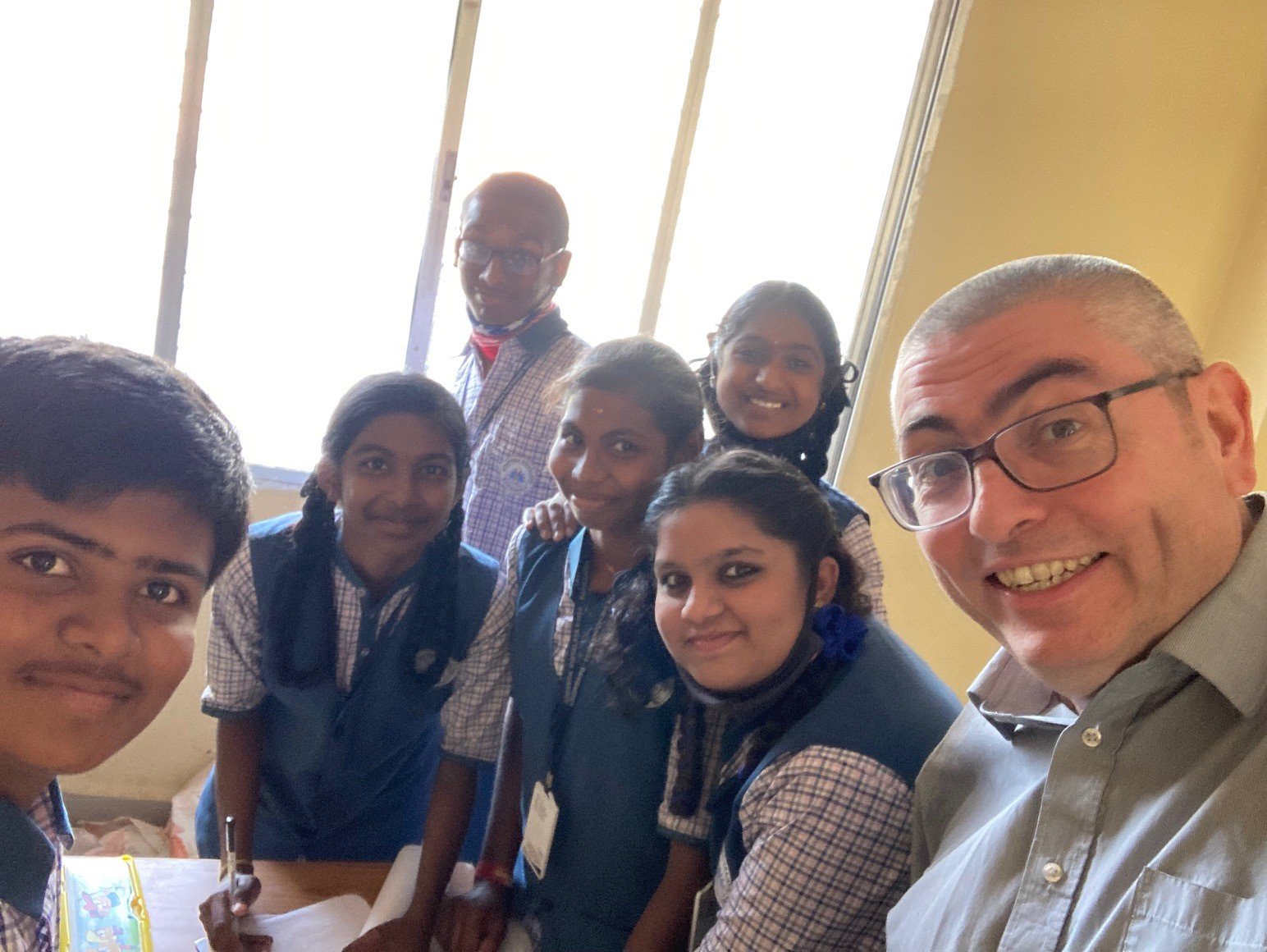

During the UK team’s visit to Bengaluru in January 2023, I spent 3 days working with Ritwika Nag and Krupa A.L from the National Institute of Mental Health and Neurosciences in Bengaluru (NIMHANS) and the staff and students of the Adarsha Vidyalaya School, Kolar. These 3 days were conceived as the first stage in the practical use of participatory video in SAMA and built on a series of online workshops we had conducted over the previous year to explore the foundational concepts of participatory video. Over the course of the workshop, the students led the production of three short films about SAMA and its impact on their school. One group produced a documentary style film, where they introduced the audience to their experience of SAMA, what the programme physically ‘looks like’ in their school, showcasing the views of students who had taken part in the programme, as well as one of the teachers in the school, a SAMA lay counsellor (Snehitharu) and the Head Mistress. In so doing, the film sought to capture the ‘whole school’s understanding of the programme, in line with the SAMA’s own ‘whole school’ approach to mental health and wellbeing.

A second group produced two short animations that explored the ways in which SAMA was supporting young people in their school to address particular challenges they might face. Aryan versus the Bullies tells the story of a fictional school student, Aryan, as he tries to find a way to escape the unwanted attention of 3 aggressive boys in his class.

Viona is Back on Track highlights the pressures adolescents can feel to achieve academically while also having to deal with other pressures at home or amongst their friends.

The films were premiered at an impact event, organised by NIMHANS, that brought together youth counsellors, child right activists, those involved in mental health promotion activities in schools and NGO personnels working with schools and children. The aim of this event was to raise awareness of the SAMA project, and particularly to highlight the importance young people’s perspective in its development and evaluation. This event was followed by a screening and focus group discussion at the school with participants in the film workshop, where participants discussed their experience of producing the videos, how the videos reflect their experience of SAMA and how they would like to see the use of participatory video developed over the rest of the project.

The films contained many fascinating insights on the young people’s perception of how SAMA is working. While the young people clearly foregrounded their own perspective, it was interesting to see from the films how SAMA was supporting a whole school approach to addressing adolescent mental health challenges. The documentary SAMA and Us takes us on a journey around the school, highlighting what the filmmakers see as the project’s most important assets. The documentary presenter points to the resources on the SAMA notice board, the ‘Speak-out Box’, where they can post notes in order to raise issues in private that can be discussed either anonymously as a group or in person with the Snehitharus, as well as the dedicated classroom where they can engage in private with the Snehitharus for these kinds of conversations. It is clear from the films that the power of SAMA for both the students and the teaching staff is the way it highlights the importance of the students own perspective on, and knowledge about, their mental health. As the headmistress makes clear, the teachers do not have all the answers. SAMA provides support that the teachers are not always able to. It is also striking in the films how SAMA seems to normalise reflection on mental health, removing some of the stigma that can surround the topic for young people, an issue directly addressed by Viona, as she seeks to overcome the strong sense of anxiety and depression she feels as she seek to maintain her level of academic achievement in the face of growing personal pressures. It is fascinating to hear how one of the Snehitharu compares the programme to wearing a seatbelt in a car. SAMA, for him, is a necessary support mechanism, to ensure that students can make the most of their education, something that the headmistress, sees as particularly important at the moment in the aftermath of COVID 19.

The ways in which SAMA foregrounds the students’ own view of the world was also emphasised in the focus group discussion, also being seen as a particularly valuable part of the filmmaking experience. Students were very proud of the fact that they had been able to interview their teachers, and set the agenda for the discussion (‘Shooting and taking teacher’s interview was the best part’ ‘It was the first time for me to take interviews with teachers. We had prepared our own questions for the teachers. SO it was nice.’) This was generally seen as an empowering experience. Participants were very proud of what they were able to achieve in 3 days, and the fact that they were able to showcase their work in and beyond their school.

It was also clear that the participants only saw our workshops as a starting point, that they wanted to develop their filmmaking skills further and had numerous ideas for more films. And this is what we need to address now. Where next for participatory video in SAMA? We are currently planning another round of filmmaking in order to further develop the youth-led evaluation of the project. We are also currently exploring further ways in which to maximise the educational potential of these films. Here we are particularly focussed on the context of their exhibition and how the films can be best curated to generate debates on the issues raised in them, with the aim of discussing how SAMA can be further developed and embedded in the Karnataka school system to address these issues, as we seek to adopt a whole-school approach to supporting adolescent mental health and wellbeing.